Helping entrepreneurs improve their succession planning

Quebec is currently going through a major period of business transfers, but many business owners neglect to prepare for this process, at the risk of having to shut down their SME. Professional financial advisors can help address this problem.

Quebec is currently going through a major period of business transfers, but many business owners neglect to prepare for this process, at the risk of having to shut down their SME. Professional financial advisors can help address this problem.

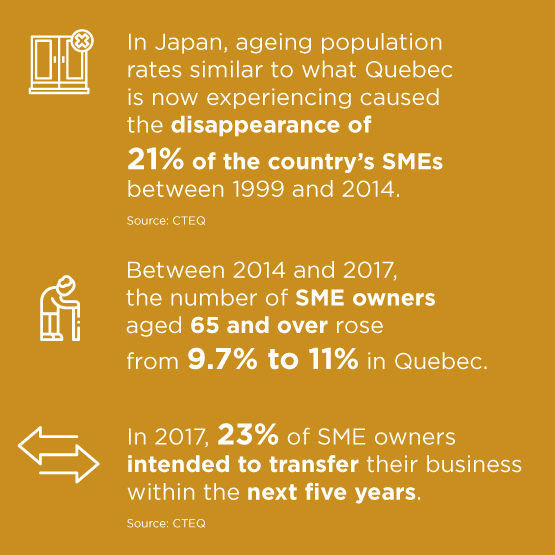

The number of Quebec business owners who are considering selling their business or transferring it to their children or employees has been soaring in recent years. In 2017, about 7,000 Quebec SMEs per year were likely to change hands, according to Statistics Canada. The federal agency’s most recent Canadian Survey on Business Conditions raises that estimate to 7,500.

“Obviously, these are just intentions and the number of transfers that actually take place is difficult to assess,” says Marc Duhamel, professor in the Department of Finance and Economics at the Université du Québec à Trois-Rivières and author of multiple studies on the topic for the Centre de transfert d’entreprise du Québec (CTEQ).

Data from the Indice entrepreneurial québécois, which Réseau Mentorat publishes each year, also reflect the generational shift underway among Quebec businesses. The share of 50 to 64-year-olds among business owners has dropped from 50% in 2019 to 31.3% in 2021,” says Rina Marchand, Senior Director of Content and Innovation at Réseau Mentorat. This is a very clear indicator of the changing demographics currently taking place.”

Three different reasons explain this increase in intention to transfer ownership. “The aging of entrepreneurs is the primary cause, which we have seen coming for many years,” says Serge Bastien, head of the team of advisors at CTEQ. “It’s the same demographic trend that’s causing the labour shortage.”

This aging of the business owner population is due in part to a lack of preparation regarding the succession or transfer of businesses. “Entrepreneurs often underestimate the time it takes to pass the baton,” says Mr. Bastien. “They think it can be done in a few months, when in fact you should be looking at two to five years.”

Not all business owners who want to sell or pass on their company to the next generation will succeed, far from it, and this will have negative consequences for the Quebec economy.

The pandemic effect

The CTEQ studies also show that business owners are more likely to consider transferring their companies when their ambition to grow the business declines, when prospects for growth decrease, or when they become less involved in the company’s operations. These factors are believed to be as important as age, if not more so.

In 2020, the COVID-19 pandemic accelerated the upward trend in intentions to transfer. The Canadian Survey on Business Conditions from Statistics Canada estimated that intentions doubled in that year. Between 13,000 and 15,000 business owners were seriously considering a transfer by the end of 2021.

“For some people, managing and operating the business became so complicated that they preferred to hand it over,” says Maripier Tremblay, professor in entrepreneurship at the Université Laval. “They were more open to opportunities that came along. And for those whose companies had increased in value during the pandemic, they wanted to capitalize on the opportunity by selling.”

Data from Statistics Canada for the first quarter of 2021 clearly indicate that transfer intentions increased more in sectors that were severely affected by the healthcare crisis. In accommodation and food services, 11.2% of owners were thinking of selling or transferring their business, compared to 7.2% in finance and insurance, and 6.9% in retail. The average for all businesses was 4.4%

Economic risk

The sharp rise in intentions to transfer poses the challenge of ensuring that these transactions are successful. “Not all business owners who wish to sell or transfer their business to the next generation will succeed, far from it, which will have negative consequences for the Quebec economy,” says Marc Duhamel.

In 2021, a CTEQ study warned that an additional 2,200 businesses could close their doors prematurely in Quebec by 2031. This “spectre of closure” could reduce the total annual sales of Quebec businesses by $20.1 billion and result in the loss of 84,000 direct jobs.

Entrepreneurs often underestimate the time it takes to pass the baton. They think it can be done in a few months, when in fact you should be looking at two to five years.

Educating clients

Members of the Chambre – and financial planners in particular – can play an important role in addressing the “spectre of closure” feared by the CTEQ. They are well positioned to educate clients on this aspect of running their companies and help them plan for the transfer.

“Entrepreneurs are driven by their projects, the place they occupy in the company, and sometimes the lifestyle it allows them to maintain,” says Luc Robert, managing partner of business agency Intégrale. “They don’t really want to think about transferring ownership, and one of the roles of the financial planner is to get them to think about it.”

One thing these professionals can do is make business owners realize that they will not be around forever and it is important to ensure the company’s long-term survival. They can start laying the groundwork by discussing whether the owner intends to move toward a family transfer, an external sale or a transfer to key employees. Each option presents specific challenges in terms of finances, taxes and the human aspect.

“Financial planners can also help business owners estimate the amount of money they will need to maintain their lifestyle or carry out projects that are important to them after selling the company,” says Luc Robert. “It helps put them at ease and do a realistic assessment of the company’s fair market value.”

Louise Cadieux, retired professor of management at the Université du Québec à Trois-Rivières, reminds us that many aspects of a transfer involve one of the main roles of professional financial advisors: ensuring the financial security of clients and their families.

“The advisor must at least have an idea of the solutions that exist, such as trusts or management companies, and of the financial and tax consequences of the various forms of business transfer on customers and their succession,” she says. “Based on this information, the advisor can develop a plan that provides security for the person transferring the business.”

[The financial planner] cannot properly support a client if they don’t know the client’s intentions for their business. This risks closing off attractive financial and tax options that require a few years of preparation.

To avoid this catastrophe, it is urgent to get business owners to better prepare for their succession. The Album de familles published in 2021 by Familles en affaires and the Institute for Entrepreneurship National Bank – two organizations linked to HEC Montréal – revealed that 43% of family businesses have no succession plan. And even among those that do, more than half are happy with an informal plan.

Overburdened by daily tasks, business owners rarely take the time to sit down and prepare for the moment of their departure. This topic is also very often synonymous with aging, which does not offer much incentive to think about it.

“We need to stop associating business transfer preparation with aging, retirement, illness and death, and instead see it as the mark of a good manager,” says Maripier Tremblay. “Even if the transaction is years away, it’s good governance to start planning. It’s a strategic issue that affects the company’s long-term survival.”

According to her, many entrepreneurs orchestrate the transfer... in their minds. They do not discuss or verify their plans with professionals, especially their financial planner. “The planner can’t properly guide the client if they don’t know the client’s intentions for the business,” says Maripier Tremblay. “This could close off attractive financial and tax options that require a few years of preparation.”

Financial planners can also help business owners estimate the amount of money they will need to maintain their lifestyle or carry out projects that are important to them after selling the company.

Conducting the orchestra

Serge Bastien believes that financial planners are in a unique position to help business owners prepare. “They see and speak to them more regularly than other professionals, such as accountants, and they tend to be long-term clients,” he says. “But I would like financial planners to refer entrepreneurs to transfer specialists more often. After 50 years, it should become fairly systematic.”

The financial planner – like other members of the Chambre – can actually play a role throughout the preparation and execution of the transfer, and even after the transfer. At the core the role remains the same: Assess the client’s situation, learn about their goals and take the best steps to achieve them using the various areas of practice of financial planning.

“Professional financial advisors must see themselves as rather like an orchestra conductor who handles the various areas of the transaction, coordinates with other professionals and, above all, integrates the business and human aspects,” says financial planner Jean-Philippe Vézina.

Marc Duhamel notes that setting up a network of experts whom the seller and the buyer can trust is often difficult. “The advisor who has earned the client’s trust can become an important link in this collaboration,” he believes. “However, I would like to see more training in business transfer for financial advice professionals, so that they are more familiar with the mechanics of these transactions and the ecosystem of transferring a business.”

Financial planners know the client’s needs especially well. They can also follow the evolution of their clients’ personal and professional lives. “They don’t replace other professionals such as accountants or tax specialists, but they can help their clients understand the strategies they propose and, above all, challenge them,” adds Jean-Philippe Vézina.

Playing matchmaker

Currently, one obstacle to business transfers is the difficulty that sellers and potential buyers have in meeting. “In Quebec there are still more people who intend to take over a business than entrepreneurs who want to sell one, so we don’t have a problem with demand,” says Marc Duhamel. “Some businesses close because their owner has been unable to find a buyer.”

The CTEQ offers a confidential networking system that helps professionals get to know potential sellers or buyers. Louise Cadieux would like to see financial planners more involved in this aspect of the process. “When they learn that their entrepreneur client wants to transfer their business one day, they should be able to get in touch with networks of professionals who have identified potential buyers,” she says.

Maintaining harmony

Business transfers also present challenges that are more human than financial. This is especially true of family transfers. “On average they are more successful than outside sales because the buyers know the company better,” says Serge Bastien. “But when these transactions go wrong, they are the most disastrous, because they put family ties to the test.”

Robert Lafond, founder of financial services firm Lafond, pays close attention to this aspect. “At Lafond, we usually suggest creating a family council, which operates with a protocol based on certain principles,” he explains. “That’s what makes it evolve from a family business to a family in business.”

Family members who are not active in the business can participate in a broader family council. This helps reconcile sometimes divergent interests. For example, those who run the business may want to focus on growing the business, even if it means reducing profits, while others may want to preserve the level of dividends they receive. “Professional financial advisors can benefit from bringing these people together in forums where they can all express themselves, in order to maintain harmony within the family and within the company,” says Robert Lafond.

The role of these professionals therefore goes far further than simply financial aspects. Maripier Tremblay invites them to think beyond their technical skills. “Ask questions about the personal lives and family backgrounds of your entrepreneur clients,” she advises. “Very often their decisions are not based solely on financial reasoning, but on personal and emotional factors. The advisor needs to understand this to determine the best scenario.”

For his part, Jean-Philippe Vézina insists on the importance of not underestimating the period after the transfer. Business owners have many major decisions to make once they receive the money from the sale. “This is the time when they will probably make the biggest investments of their lives, those that will ensure their future,” he says. “They also have to plan their estate, and sometimes rewrite their will or revise their insurance coverage. This is the heart of the financial planner’s role.”

Professional financial advisors must see themselves as rather like an orchestra conductor who handles the various areas of the transaction, coordinates with other professionals and, above all, integrates the business and human aspects.